A large steep slope in the Barry Arm fjord 30 miles (50 kilometers) northeast of Whittier, Alaska has the potential to fall into the water and generate a tsunami that could have devastating local effects on those who live, work, and recreate in and around Whittier and in northern Prince William Sound.

View the current status update

Initial research indicates that other communities and infrastructure in Prince William Sound may also be at risk of a measureable tsunami and dangerous currents, including Valdez, Cordova, Tatitlek and Chenega.

At this time, there is no way to know when, if, or how much of the slope may fall into the water. Because of this challenge, State of Alaska and Federal science and emergency management teams are developing tools to provide monitoring and alerting capability for a reliable early-warning and rapid-detection system for the potential risk from a Barry Arm landslide and tsunami.

We strongly encourage you to take this threat seriously and avoid this part of Prince William Sound. Stay off this slope. Rockfall has been observed in this area. Please heed U.S. Coast Guard safety information and remember your natural, early-warning signs for a tsunami may be your best and only alert.

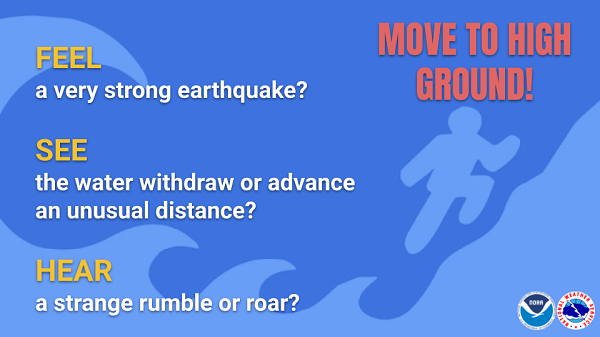

Your natural warning signs may be your most reliable and fastest alert. - Tsunami.gov

The National Tsunami Warning Center will issue a "Tsunami Warning" if a landslide occurs that produces a detectable tsunami.

DO NOT rely on only one type of alert system to receive this important information. You may receive a warning over:

A Tsunami Warning means you need to take action immediately! You must move quickly. Stop what you're doing and move inland (away from the coast) and head to higher ground. You will not have time to reach deep water from the harbor. Dangerous coastal flooding and powerful currents will be possible for several hours.

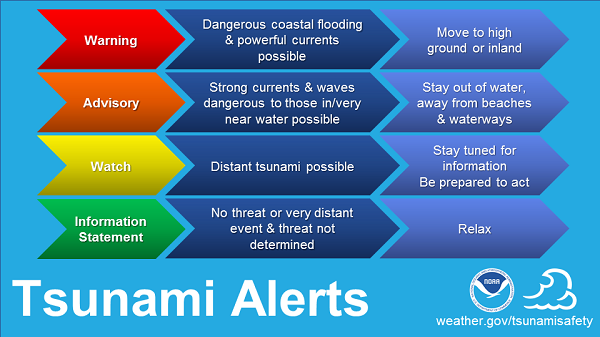

Tsunami Alerts indicate the level of threat, and the appropriate responses, on an escalating scale.

While geologists can clearly identify the region is at risk for a landslide, there is much they don't know about the situation. It is difficult, if not impossible, to predict with any degree of certainty. Scientists are working to gather what information they can, to help them better understand the risks, and to better guide any emergency communications and response.

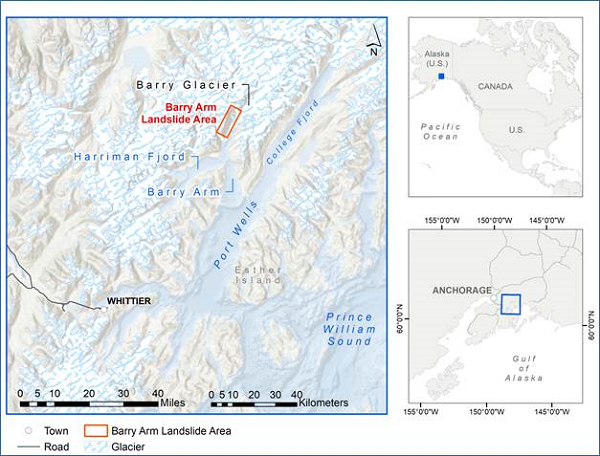

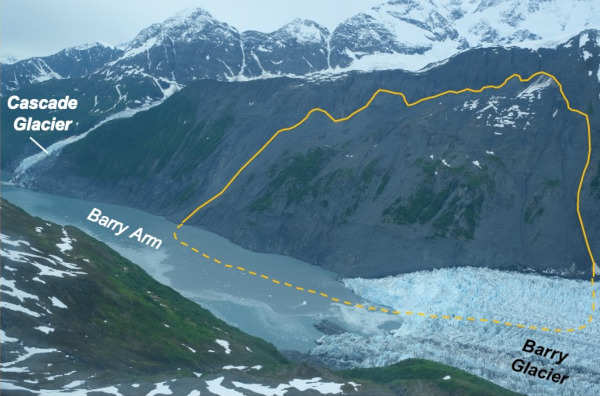

The unstable slope that could produce a landslide is located on the west side of upper Barry Arm near the terminus of Barry Glacier, northwest Prince William Sound, Alaska.

Barry Arm is located in Southcentral Alaska, about 60 miles (100 kilometers) southeast of the state's largest city, Anchorage, and about 30 miles (50 kilometers) northeast of Whittier, the nearest community, with a year-round population of about 200 residents.

A fjord is a glacier-carved narrow inlet of the ocean between two steep slopes. In many parts of Southcentral and Southeast Alaska, a fjord leads to the toe of a glacier that reaches the ocean, called a tidewater glacier. Thanks to the numerous glaciers that once covered Southcentral and Southeast Alaska, the state is home to a great number of fjords.

The Barry Arm fjord is in an area referred to as the "accretionary prism," where plate tectonics forced sedimentary rocks to collide and merge with the southern shore of the Alaska mainland long ago in geologic history. This process created numerous fractures and faults in the bedrock, and the subsequent, multiple glacial advances further fractured and eroded the landscape.

As alpine permafrost thaws and glaciers thin and retreat, support of the valley walls is degraded and removed, allowing rockfalls and landslides to occur; landslides entering the water have the potential to create tsunamis.

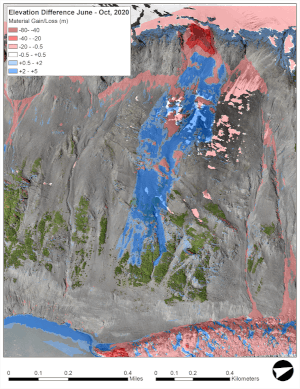

Click for higher resolution image.

Image credit: Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys (DGGS)

Comparison of two lidar-derived elevation models for the Barry Arm landslide mass reveal a significant rockfall (64,200 cubic meters) on the main body of the landslide. The event was recorded by the nearby seismic station—thankfully it was unharmed. Slow, widespread movement of the landslide mass identified using satellite radar is also confirmed by the repeat lidar scans conducted in late summer/early fall.

The unstable slope in Barry Arm is located in an area of steep, glacier-carved terrain where the glacier has recently thinned and retreated and the bedrock is highly fractured. While the slope moved about 600 feet (180 m) toward the fjord between 2009 and 2015, its motion has slowed in recent years. Data from scientific observations in June and July 2020 indicate the slope movement was less than a few inches (centimeters) during that period, suggesting that the risk from a potential landslide-generated tsunami is lower now than it was between 2009 and 2015.

As of Summer 2020, there is a great deal of information that is currently unknown. Research continues and efforts to monitor this slope with satellite and airborne sensors, and with sensors attached to the surface and buried into the slope are ongoing. Satellite monitoring will continue until fall, when snow will cover the region around Barry Arm.

This view looking northeast into Prince William Sound's Barry Arm shows the unstable slope area, outlined in yellow, which geologists believe has the potential to produce a tsunami-generationg landslide, (photo by Gabriel Wolken, June 2020).

We don't know when a landslide and resulting tsunami will occur.

This type of risk in Prince William Sound is not new, though we are now acutely aware of the situation in Barry Arm today. There are many fjords in Prince William Sound and Barry Arm is one of many unstable slopes in the region.

At this time, we have no indication that a landslide is imminent, but landslides can happen at any time, and those who live, work, and recreate in Prince William Sound need to remain vigilant, have several ways to receive emergency information, and be ready to move to high ground with little to no warning.

While we are preparing for the possibility that the entire unstable slope could fall into the water, there are other possibilities ranging from no future movement to rapid full failure of the entire unstable slope. The possibility of any amount of landslide movement producing a tsunami is real, and could occur without warning.

Scientists and emergency management experts are working to study, monitor, and inform people who live, work, and recreate in Prince William Sound to keep people safe while working to protect local infrastructure.

Multiple state and federal agencies and institutes are working together to collect baseline data that will help them understand how big the landslide area is, whether or how much it is moving, and how big a tsunami could result from a landslide.

Currently, scientists are monitoring motion by comparing data on the site collected at different times using a variety of scientific techniques. These include satellite-based radar (satellite interferometric synthetic aperture radar), airborne lidar (a kind of radar using light pulses instead of radio waves), and aerial photograph-based mapping (photogrammetry).

Satellite radar data was collected in May, June, and July 2020 and airborne lidar and photogrammetry surveys were collected in June 2020. This work generated high-resolution imagery and topographic data for detailed mapping and analysis of the unstable slope. Repeat airborne lidar and bathymetric data collection in upper Barry Arm is planned for fall 2020, and the resulting data will be published on this website and in government social media sites. All these data will help generate more accurate scenarios of landslide-generated tsunamis originating from Barry Arm.

High-resolution orthoimagery (left) and shaded digital terrain model (right) of the main slope instability at the terminus of Barry Glacier. The data used to create these products are from airborne photogrammetry and lidar campaigns conducted in June 2020.

There are plans to install tide gauge stations in the Barry Arm and Port Wells region to monitor for a tsunami should a landslide occur. New bathymetric surveys are planned for August 2020 to help scientists better understand the underwater sea floor and how it would affect a tsunami should a landslide occur.

Scientists are meeting routinely to discuss their observations, share information about any notable changes, and share this information with emergency management agencies.

This webpage will be updated as new information becomes available. It will also carry agency-coordinated press releases, email alerts, and social media posts with new information about the Barry Arm Landslide.

Many coastal areas in Southcentral and Southeast Alaska are susceptible to tsunamis generated by landslides, and history records several such events, including the 1958 Lituya Bay and the 2015 Taan Fjord tsunamis.

The Lituya Bay tsunami was generated by a 39 million cubic yards (30 million cubic meters) landslide, triggered by a Magnitude 7.8 earthquake on the Fairweather Fault on the west side of Glacier Bay National Park. That tsunami contributed to the deaths of two people.

The 2015 Taan Fjord tsunami was generated by a 99 million cubic yards (76 million cubic meters) landslide that occurred following retreat of the Tyndall Glacier. The wave affected the entire length of the fjord.

Within Glacier Bay National Park, a slope on the north side of Tidal Inlet has been slowly moving since at least the early 1900s, but has never catastrophically failed and entered the water.

The Barry Arm landslide is about 1.4 square miles (3.7 square kilometers), with an estimated total volume of approximately 650 million cubic yards (~0.5 cubic kilometers), or roughly 6.5 times larger than the landslide at Taan Fjord. It is not known how much of this landslide volume would enter the water during a potential rapid failure. (For a graphic depiction of the relative size of Alaska's largest tsunami-generating landslides, see this letter.)

Analysis of airborne and satellite data reveal motion of the landslide beginning as early as 1957. Between 2009 and 2015, the landslide moved 600 feet (183 meters) toward the fjord at the same time as Barry Glacier was thinning and retreating below the landslide. Since 2016, the landslide rate has slowed; recent analysis of satellite radar data shows landslide motion during the period June through September 2020 was less than a few inches (centimeters), but between October 9 and October 24 eight inches (20 centimeters) of downslope motion was detected.